This is a short memoir about a long memoir.

I’m writing it now because otherwise, I will never write it no more. Like, if you don’t do it, would you ever do it?

I mean…you know what I mean. Like they say about relationships, “It’s complicated.” My developing relationship with my memoir is kinda complicated.

When I first started writing my non-celebrity autobiography, I didn’t know much about it. I mean, about my biography. Why write it? Why not leave it alone? Who’s is gonna read it? Like, what have you got so special in your fifty-some years of non-millionaire’s life that people would actually spend a few hours of their time to know who you are, and who you are not?

Why would they care?

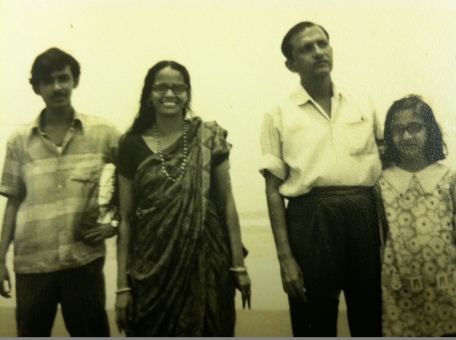

Like, okay, you are a first-generation immigrant from a poor, Brahmin family in Calcutta. So what? Ain’t everybody in Calcutta poor? What’s the big deal? Like, didn’t we see City of Joy, or Slumdog Millionaire? Okay, Slumdog wasn’t Calcutta. But isn’t Calcutta even more Goddamnpoor? And you were not even that poor. Like, you never starved or anything. You never lived in a slum. You never didn’t not go to school. You didn’t do no drugs or gangs and stuff.

Okay, so you’re gonna tell us another rags to riches story? Don’t we have enough already? And what’s this nonsense about Brahmin and poor? Brahmins are the uppermost caste in that wretched caste system, ain’t it? Brahmins and poor?

Gimme a break!

These are questions I imagined people here in America would ask me, or for that matter, I thought, today’s young, Americanized people would ask even from Calcutta, Bombay, Bangalore or Bangladesh. So, after I wrote about sixty or seventy percent of my memoir in English, I stopped. I played up my impoverished childhood, and I played up my beautiful childhood. I played up my violent young adulthood in a violent political turmoil in Calcutta with bombs and murders and rapes and stuff, and I played up my fascinating, almost spiritual young adulthood in Calcutta, oh God, with surreal descriptions of monsoon rain and Diwali firecrackers and all-night train rides and wildflower collections and cricket matches. I played up my mother’s painful death of cancer when she was forty two, and I played up my love affairs with beautiful Bengali girls — a few real and most others imaginary — and even included dream sequences lush with lovemaking, as if in anticipation of someone like Ron Howard or Miyazaki would snatch it from the Union Square Barnes and Noble immediately after it was put out on sale.

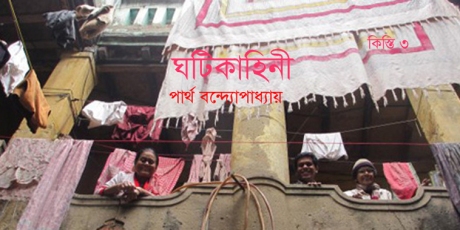

Ah well. Too much expectation. Too little reality. After I had the first couple of chapters professionally edited — ready to go to publishers and literary agents — I stopped. And then it dawned upon me that perhaps I should write in a language that is more lucid to me than lexicography. And I began writing in Bengali. Bangla, that is. And it got picked up immediately by an online literary magazine, and lo and ho ho ho, each 3,000-word episode got 2,000 hits! It was a memorable memorabilia.

Facebook friends even sent in confidential kisses.

So, after all, people do want to read it. That was my realization.

And now it’s all ready to come out as a book. The publishers are even showing interest to hold a press conference in Calcutta, and guess what, a session of selected readings from some of the chapters I wrote. Like, they’re going to make me famous. Rich…well we’ll see. But famous…I shall take it even at two o’clock in the morning…in my dreams or not.

Writing from your heart helps. Blood, sweat and tears trickle from your pen…I mean…the friction point between your fingertips and keyboard squares. Love, passion and honest, no-sugarcoating, no-glossover tales still matter to most people. This is my new, gratifying realization.

There’s gonna be a time, not too long after, when people will stop reading. Just the same way people have stopped writing letters. Love letters. Letters to your favorite sister. Letter to your best friend. Like, those letters I wrote when I first came to America thirty years ago — in August of 1985. When I felt like I was Neil Armstrong dropped on the moon: a vast, barren, empty, gray place where you’re completely alone. Completely alone. I wrote my letters then as if a forever-exiled prisoner writing his script, and putting it carefully in a stoppered bottle, and floating it away, adrift on the turbulent sea, hoping that some day, it will surely reach those people you left behind forever — people who loved you and never wanted you to leave. Words came from the deepest places in my heart, and words came as if God was sending his message through your lips. I knew I was being honest.

I knew I was being honest, when I wrote my memoir. I knew I was being totally naked in front of my God.

I knew I was doing it, perhaps for the first time in my life.

Sincerely Yours,

Partha

Brooklyn, New York

###

Love the way “the friction point between your fingertips and keyboard squares” expresses your “love and passion” for writing about yourself and people who made your life what it is today. Thanks for bringing back memories about letters that I once used to pen with love and passion to people who mattered. Eagerly awaiting the release of your Bengali memoir.

Thank you for your kind and encouraging comments. The book will come out on December 29 in Calcutta. All of you are invited.